Doing Architecture - An Introduction

Much discussion around system architecture focused on architecture as a property of a complex system. A system has an architecture and that architecture has pros and cons. What tends to be less well covered is the activity of doing architecture.

As the complexity and capabilities of a distributed software system grows, so too must the complexity and capabilities of the organization supporting it. At some point the stakes get high enough that architecture ceases to be a property of the system structure decided on the move and starts to become a distinct activity.

This transition may seem simple enough at first but as time goes on the sheer number of things the person wearing the architect hat has to consider can become overwhelming for them and the wider organization. This series of articles is my attempt to reduce the stress of figuring out what needs figuring out and provide a set of document templates that form a cookie-cutter starting point for establishing an architecture definition process. It's aimed at smaller organizations wanting to establish an architecture capability, with or without a dedicated architect role, and at any engineers needing to tackle architecture for more complex systems.

In this introduction I'll introduce some concepts, outline the process from a high level and list some things to think about before getting started. Subsequent articles will each address a major pillar of architectural planning and give templates for documenting it.

Architecture Definition Process

I've chosen to cover this topic in detail in a separate article titled Iterative Architecture as this one is plenty long enough already but I'll include the key points here. This section assumes an agile development process but if you're practicing Waterfall it should still have some value.

Our two main objectives with our architecture process are to eliminate as much risk as possible as soon as possible and to integrate with agile engineering processes. Risk leads to fear and fear creates resistance to change. Without change, there's no need for architecture. The linked article gives guidance as to what sort of decisions carry the highest risk.

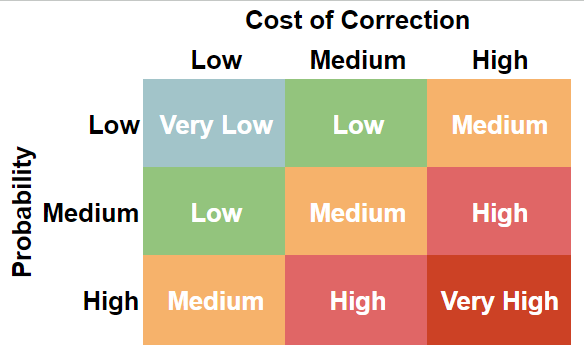

For our purposes, risk can be defined as the probability that a requirement, decision or course of action (guided or unguided) eventually turns out to be incorrect multiplied by the impact or cost of correcting the mistake when that time comes. I emphasize when not because it is inevitable but because over time the probability of a mistake tends to reduce ("so far so good") but the cost of correction tends to increase with your investment of time and effort. Below is a standard risk matrix showing calculated risk level for our two inputs.

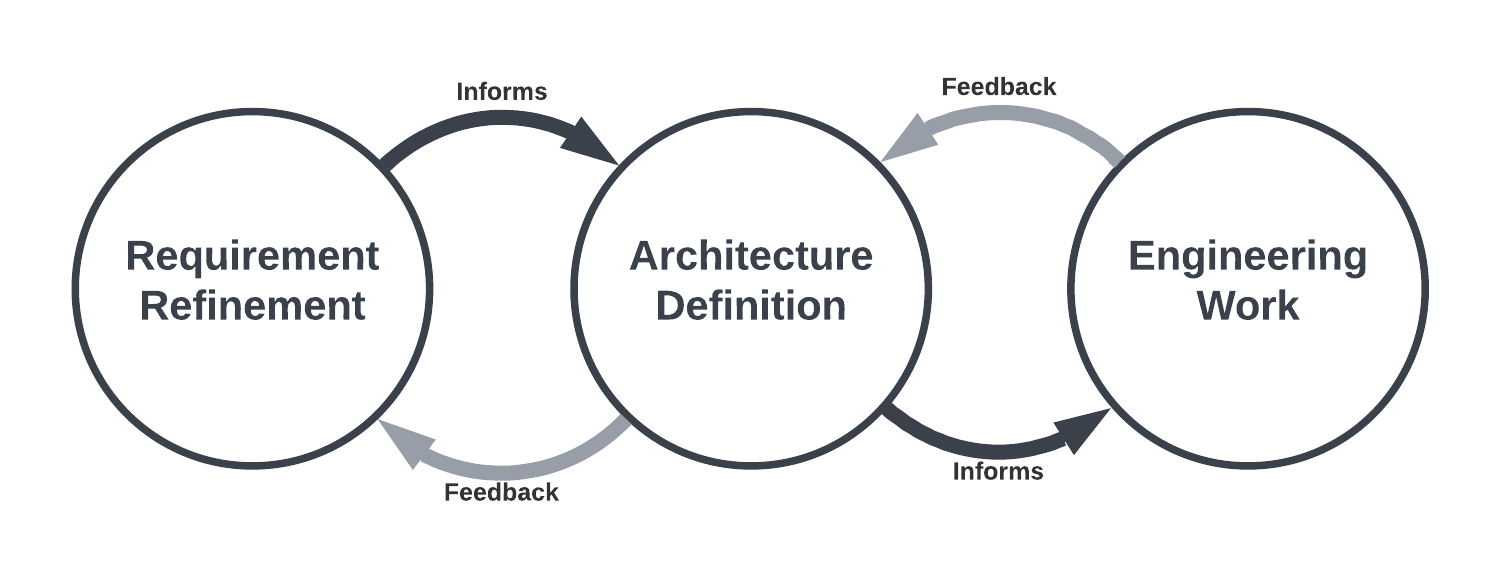

So we must refine our requirements, refine our designs, gather feedback and repeat, in order of descending risk, while staying at least one step ahead of development work. Our design iterations provide value in the form of mitigated risk and much like we must tackle groundwork in early development iterations, our early iterations will be the biggest and deliver the highest value.

Your first iteration of your requirements and design, tackling the highest risk decisions, will warrant a mostly theoretical review. This means walking through it with stakeholders and gathering feedback based on theory and experience. Two or three iterations in there should be enough risk mitigated for development to start. There will still be some uncertainty and 'mistakes' may be made but we accept this trade-off in exchange for progress and real-world feedback. If you tackle the big risks early, the costs of these mistakes should be low or very unlikely.

Capturing the Architecture Definition

Defining architecture is a deeply collaborative process and we need somewhere to centralize our requirements, designs and decisions in a cohesive way so that everyone can be quite literally on the same page. The Architecture Definition (AD) is a document (or set of) that tackles this in a consistent, repeatable way. Our AD will be comprised of a set of Views, each one focusing on a single dimension of the architecture. When combined, these dimensions create the full model of an architecture illustrating functionality grouping, infrastructure, concurrency and process design, data relationships and much more.

"If you don't know where you are going, any road will get you there"

Lewis Carroll

AD Sizing

There is a limit to how much information can be captured in a single AD document, though this doesn't really equate to an 'amount' of architecture. A large modular monolith can produce a large, dense AD and a medium sized microservice system can produce a small, sparse AD.

We want to keep our documents comprehensible and the best I can do is to say that you'll know 'too big' when you get there. There are a few ways to tackle this but the simplest is the use of appendices. If your requirements section gets too big or you find yourself producing five security diagrams in a single section, these can be moved to an appendix document and linked to. People's attention spans are dwindling and your stakeholders are likely busy people so you should aim keep only the information critical to the majority of stakeholders understanding the architecture at a high level and how it addresses the core requirements.

If the information density stems from the complexity (lots of elements) of the system under design, consider creating nested AD documents, each defining a logically distinct part of the architecture and keeping the root AD as a high level overview of how it all fits together.

If you find yourself compelled to include lots of technical detail or application-scale architecture, consider introducing a Component Design document type. This can be much more free-form and sit under the AD. These can be used to capture things like detailed API definitions, code snippets, application structure or suggested coding patterns.

Reality vs Aspiration

This question has come up more than once in my career so I figure it's worth mentioning. Does an architecture document define what is or what will be? This can seem like a 'the chicken or the egg' conundrum but, like that puzzle, it does have a logical answer. Your architecture documentation should always be written as aspirational, defining the destination. If reality deviates from your designs, the reasons for this need to be captured in your documentation and the designs adjusted as if the reason had been known in advance. You have to hop in a time machine and justify the new reality before it happens.

This is an important part of the processes and often happens thanks to the feedback loop from engineers. Initially this feedback might take the form of "that won't work because X" but as your system and organization grows, you may start delegating localized architectural decision making to engineering teams and start receiving late-stage feedback like "we actually decided to go with database X instead of Y". Do not see this as a loss of control, decentralized decision making is critical to scaling the system, organization and your architecture process. Simply capture the reasoning and if it's sound, incorporate it into your designs as if it was always known.

If you're working on a brownfield project or introducing architecture documentation to an existing system post-hoc and the migration from reality to aspiration presents challenges that needs to be planned for, this work should go in an appendix document. If it's a considerable journey ahead you should position your AD as a migration architecture halfway between the current reality and long term aspiration and then either evolve or supersede it once achieved.

Views

The architecture definition framework laid out in this series is based on (though grossly simplified) the Views & Perspectives model defined in Software Systems Architecture with some terminology borrowed from the 4+1 view model, which also informs our set of 'core views'.

Each View addresses a key dimension of a system architecture (logical structure, physical structure, etc.) and contains at least one model (diagram) strongly focused on the concerns of that View. The templates in subsequent articles will each produce a single View and can be refined for your specific problem-space and organization. Not everything in each template will be useful for every solution but should serve as a good checklist before deleting.

Our set of core Views will be Context (encompasses the Scenario view from 4+1), Logical, Process, Development and Physical. Later articles will deal with Views like Information, Operational, Risk and Security.

Perspectives

Each Perspective addresses a cross-cutting concern (performance, security, availability, etc.) in the context of each View. The purpose of 'applying' a perspective to a View is to validate that the models and designs in that View properly support the desired quality. We evaluate the models in a View from the Perspective of someone concerned about a specific quality.

The act of applying a Perspective to a given View will vary in value, effort and output. In some cases, it will be a simple mental exercise or a pen and paper diagram for your own peace of mind. In others, particularly Perspectives addressing priority quality requirements, it will yield a more formal diagram that should be included in your documentation.

For example if we have an infrastructure diagram as the primary model in our Physical view, applying the security perspective will produce a separate diagram detailing things like firewalls, mTLS or authentication and authorization policies between cloud resources that didn't fit in the original infrastructure diagram.

View Consistency

The models and designs in each View can themselves be 'applied' to other Views in a similar manner to a Perspective with the aim of ensuring they are consistent. Your Logical model may have a service calling out to a third-party system but your Physical model has it on a network with no egress. Your Security Perspective for your Physical View may have been touting this lack of egress as a benefit.

A helpful exercise here is to do some pen and paper sketches combining the one-dimension models into a new two-dimension 'Logical-Physical' or 'Process-Data', as examples. The outcome of comparing Views is normally the refinement of existing models rather than producing anything new and any such sketches don't need digitized. This is an important activity to engage in early and continuously as the oversights it can highlight can be pretty fundamental.

Decision Records

A decision record is a document that captures the context, reasoning and outcome of an architecturally significant decision. While this practice undoubtedly delivers a lot of value it can be challenging when starting out to reliably identify which decisions truly warrant such documentation.

"You can't really know where you're going until you know where you have been."

Maya Angelou

The purpose is largely to record your reasoning for posterity and avoid repeated mistakes or someone taking it upon themselves to correct something they perceive as a mistake later. We should, however, aim to justify the majority of significant our decisions in our AD itself, not least because it's the first place people will look. You may want consider decision records for the highest risk decisions you tackle early in the process as a way of capturing extra detail and link to them from your AD so they are discoverable.

Given the target audience for this series and the aim of keeping things lightweight, I will be omitting formal decision records from the process and will instead give examples of using call-out segments in the AD document. If you think your organization would benefit from a formal decision log, take a look at https://adr.github.io/ and put together a template that suits your needs.

Establishing the Architecture Capability

Depending how mature your organization's architecture capability is, you may want to take the time to get some foundations laid. For an exhaustive (and definitely excessive) list of considerations and inspiration on this topic check out the TOGAF ADM model's Preliminary phase. To start, you should just consider the following.

Documentation Repository

You should settle on tools for writing and storing your architecture documentation before you get going. This can be an online tool like Confluence or Notion for an out-of-box solution or a markup language like markdown or asciidoc in conjunction with a source control repository. You should find tools (or build one) to publish your markdown as an internal website to aide dissemination and accessibility.

Architecture documentation should be centralized rather than trying to co-locate it with any source code or technical documentation. As time goes on, your architecture repository will swell and needs to be free to find it's own structure. This series focuses on the 'main character' of the repository but the cast may include reference material, investigations, patterns, architecture principles, detailed decision records and more.

If your organization has business- and engineering-focused documentation spaces it is important to maintain traceability from architecture documentation back to the former and from the latter back to architecture documentation with links. Documents will move and be renamed over time so do give thought to how you will maintain the integrity of your links if you're self-hosting.

Modelling Notations

Consistency in the use of modelling (diagram) notation is important. I strongly recommend adopting C4 and UML from day one. The latter can cover nearly all of your requirements, while the former creates more information dense diagrams well suited to technical audiences and small, low risk or time constrained solutions.

Online tools like draw.io, lucidchart and icepanel make for an easy start and can provide easy collaboration but do consider compatibility (from a workflow perspective) with your chosen documentation approach. Screenshotting and pasting diagrams into Confluence for want of an embedding feature can get tedious and makes it difficult for others to find and modify your diagrams later.

Diagram-as-Code tools like Mermaid and PlantUML have been gaining better support for a while now and are a great way to open-source your work within the organization without buying everyone a license for some tool. They are supported by a lot of markup renderers and online documentation tools, have a reasonable learning curve and can streamline the editing process.

Ultimately you will probably find room for both solutions in your process, either mixing and matching based on the type of model or using DaC for prototype diagrams in the initial stages when edits are frequent and then producing a richer, higher quality diagram in something like lucidchart once you have a high degree of confidence in the model.

Basic Principles

Establishing a set of architecture principles is an important topic but outside of this scope of this series. The point of defining architecture principles is to distill your organisation's or product's core goals, values, risks and strategy into a set of guiding principles that will then feed into later decision making. They range from abstract enterprise-level concepts down to concrete engineering practices, often with traceability. The latter should be your focus to begin with.

As a simple example let's imagine you're working in an organizational context where if you were to leak customer data you expect to be fined into oblivion. Most businesses don't love getting fined by regulatory bodies and this is a legitimate business risk that should be considered explicitly (you will, in fact, often see this stated in a set of enterprise architecture principles). To protect against this you might define a principle stating that user data must only be accessed via the service that owns the data to enable effective authorization and another stating it must never be replicated or persisted elsewhere, including event streams, without suitable encryption.

As another example, your company may be against the clock to get a product to market. It may then be wise to define engineering principles standardizing as much as possible (JSON & REST for every interface, URL based API versioning, PostgreSQL for every database) to limit debate, experimentation and up-skilling in the short term. You might also want to define principles that encourage the qualities that support sustained velocity like maintainability, testability and deployability.

This is not a strict prerequisite for doing architecture work but as your organization grows, these principles become very helpful to engineers and others tackling architecturally significant decisions. I suggest you at least chip away at this in the background. At the very least you'll discover a lot about the business and that will help with your architecture work.

Integrating With Engineering

As mentioned earlier, figuring out how to slot architecture work into your organization's delivery process without blocking engineering work is a challenge and you should tackle it early. If allowed, the architecture definition process can draw out into a near never-ending refinement process and, as an architect, you may feel an expectation for you to produce a complete, watertight architecture specification before development commences. This, though, does not work with iterative agile development methodologies.

Read through my iterative architecture article and see if you can derive some inspiration, do some more research, read the rest of this series and then circle back to this point and sketch something out that works for your team. Walk through it with your colleagues, explaining the goals and asking for ongoing feedback so you can measure it's suitability and refine it over time.

And we're done! Some of the concepts here may not fully make sense yet and that's OK. I may have put the cart before the horse a little. Things should become a lot clearer as we look at some document templates and examples but you might want to circle back to this primer later to help gel everything together.

Next Up: in progress